PROJECTS

Machloket: a disagreement for a greater good

Machloket: a disagreement for a greater good is a community storytelling project created with Jewish communities groups across the UK to amplify marginalised voices, highlight and celebrate diversity and offer both a broad and intricate picture of what it means to be Jewish in the UK today.

The project is created by Jewish artists Nick Cassenbaum (take stock exchange Co-Artistic Director) and Tash Hyman and is being delivered by us take stock exchange, with support from The Royal Court Theatre (London) and Arts Council England. So far we’ve met with 30 different community groups, including over 200 people from all over England - from London to Manchester, from Bradford to Truro, and Liverpool to Norwich.

We are creating a podcast to share the incredible stories we’ve been gathering - you can listen to the first to episodes here. Each episode features a selection of groups and looks at themes like exclusion and community, memory and migration, ritual and legacy, and hope, belonging and joy.

Longer term, we aim to create a theatrical performance which will tour to community spaces across the country - watch this space…

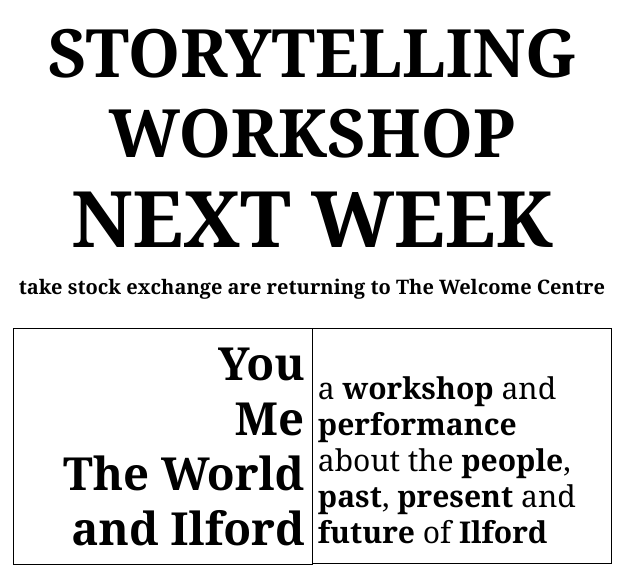

You, Me, the World & This Moment

During the first half of 2022, we visited communities across East London, and asked people to talk about their experiences of the pandemic, and how they were looking forward to the future. We’re living through an extraordinary moment, one which people are experiencing in wildly different ways. This project is about making space to reflect on that and share our thoughts, ideas, stories and experiences with our neighbours.

In the summer we held our first live event since the pandemic began at Poplar Union. You can now hear the stories we told and some of the conversations we had throughout the project in two special podcasts. Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts - Spotify, Apple, Google and elsewhere!

The music throughout the project is by Anna Lowenstein and the podcast is produced by Penny Bell. You, Me, the World & This Moment is supported by Arts Council England, Poplar Union and Vision Redbridge.

Episode 1 - You, Me, the World & This Moment - powered by Happy Scribe

Hi there.

This is Olly from takestock exchange here.

What you're about to listen to isan edited recording of an event

that happened at the Poplar Unionthat formed a culmination of a project we

delivered over the first half of 2022,called 'You, Me, the World & This Moment'.

The project consisted of us visiting lots

of different community groupsfrom across East London and asking people

to talk about their experiencesof the pandemic, how they were feeling now

in this moment and how they werelooking forward to the future.

And what you're about to hear is sixstories told by me and Nick Cassenbaum

with musical accompanimentfrom Anna Lowenstein that we created as

a result of those discussions and also some of the people who are present

at the event at Poplar Uniondiscussing these stories, enjoy.

Okay everyone, so in a moment,we are going to tell you

six stories in two sets of three,and these six stories are about what

happened when we went to different community groups 'all over East London

and asked the people therethe same four questions.

Okay, we're going to tellour first story now.

And this story is called 'One Rule for Oneand Then Another rule for Another'.

This is our honorary member.

The phrase is shouted across the room.

We are at an all male social club,at their weekly gathering.

The meeting takes place in a small

community room, nestled at the heart of a housing estate somewhere in Poplar.

The members are making each other cups

of tea and chatting about a few different things.

One, sitting proudly in his wheelchair,

wearing a West Ham shirt,seems to bring every avenue

of conversation back to his beloved teamand lets each person who walks in hear

the latest chant he'spicked up from the terraces.

Some of the members thought today's

meeting was going to be about prostate cancer.

No, Nick and I have to explain a number

of times to people as they come into the room.

That's not what we'rehere to talk about today.

There's a look of reliefon people's faces when we do.

And this is especially true

of the honorary member who's just walked in, who, as it happens, is a woman,

hence her membership of this all malesocial club being honorary, I guess.

So what usually happens at your meetings?Says Olly.

The group's facilitator, an older man,

bright faced, big moustache,explains that Sometimes we just talk,

sometimes we play music,sometimes we play games.

Not kiss chase, says the honorarymember There's laughter.

So what's in your mind today?

Says Olly.

Sex, says the honorary member.

A man with a very loud,

kind of high pitched voice cackles, cheers and bangs the table.

No, not really, she says.

I've just come from work mode

and I'm a bit stressed, been on the new tills all morning.

She wears a Marks and Spencer's workersuniform, hair pulled back into a ponytail,

black polo neck shirt with the M&S logo,black trousers.

Her black face mask was hanging from one ear as she came into the room,

but she's since taken it offand carefully placed it on a piece

of tissue paper that'son the table next to her.

Nick got his top from M&S, Olly says.

Yeah, me too, she says,pointing at the logo on her uniform.

Everyone laughs again.

When this pandemic started,

I was quite annoyed, says the man with the high pitched voice.

His voice is very loud and there'ssomething about it that makes it sound

like he's either delighted oroutraged at everything he's saying.

Because when I found out about all

the government saying this, that this, that, this, and yet they was doing

differently totallyfrom what we were doing.

And to me, it's just annoying.

I just feel sorry for all thosepeople who lost their lives.

It's just ridiculous.It really is.

Yeah, I've lost a couple

of members of family, says the honorary member and then my son

got it and he has asthma and then again,he was on his own and I couldn't go down

there or anything, you know, to help him out and that.

The man who runs the group tells us about

his sister, who's got leukaemiaand has been isolating for two years.

You get to our age, he says,and it could be around the corner.

That's why we have a laughand a joke in here.

You never know, do you?

This is the place where we escape.

The rest of the room shouts, yes!

And there's more loud, distinctive laughter.

The man with the delighted,

outraged voice says, there are vulnerable people who live

alone, how can we helppeople we don't know?

And those people who don't wear masks

to look after other people,what does that say about people?

The honorary member takes over.

Do you remember when COVID started

and it was mandatory to wear masks wherever you went right?

And at the time, some of us were standing on the doors to make sure

people and that,come in and had their masks on.

Where my story is we're right across

the way from the Walkie Talkie building,right in the centre of the office people.

You'd be surprised howmany rude people there is.

One of them even told my colleague to

F off off just for askinghim to wear a mask.

One evening, I was goingto do the late shift.

I politely asked a womanto put one back on.

She really gave attitude.

It really pissed me off.

Takes a lot to get me angry.

Then about 15 minutes later,I see her coming my way.

So I like to turn my back slightly,so I couldn't see her.

But you know what?

She come up to me and apologised.

She said, I'm sorry for the way I spoke

and I thought, Why can'tmore people be like that?

Do you know what I mean?

It does make you think, says the man with a delighted, outraged voice.

What does it make you think?

There can't be one rule for one,then another rule for another.

But clearly there is.

It shouldn't be like that.

The man who runs the group has been

sitting, listening, twitching, grunting agreement at different moments.

But now he jumps in.

It's all about the social contract,he states emphatically the softness

of his Salford accent giving wayto something more declarative.

We all live in a society,

but there is this idea that you asan individual can do as you please.

But this virus don't play that game.

Your actions have consequences.

So even if you think you haven't got it,you might be spreading it to someone else.

So what you do impactson what other people do.

It's like the politicians.

They can't say, you must do this, butactually I'm going to do something else.

People say it's my life, I'll do what I please.

But it doesn't work like that.

You can't go around shooting people,you can't go around libelling people,

you can't run into a cinema and shoutFire because it's your right.

Everything you do has a limit.

And people, he says,should look after each other.

Okay, this next story is called'That felt good, being a rebel'.

People who lost their job becauseof the pandemic are now struggling.

Food banks, shops closing, who would havethought Debenhams would have shut down?

The high street is getting so empty.

We're on a zoom.

This is a group of writers that usuallymeet in person at a library in Redbridge.

We've met them many times before,but never on zoom.

But since the beginning of the pandemic,they've only met online.

The woman who runs the group is talking.

Her face is framed with thick blackcurly hair and dark rimmed glasses.

She sits in front of a stark white wall,quite still, quite held.

But her face is always somewherebetween a half smile and a big grin.

I think it's changed the world.

I think people have also worked out howimportant contact is, human contact,

the importance of touch,seeing people face to face.

I've been in lonely placesbefore, I've been isolated.

Essentially, we are group animals.

We're not meant to live in isolationand zoom and meeting people.

It's not the same as actually givingsomeone a hug, unless you break the rules.

Did you ever break the rules?

Yes, she answers without leaving a beat.

Seeing my kids, my older daughterhad been living in America.

As soon as I saw her,of course I gave her a hug.

It's horrible otherwise.

It's the turn of a womanwho has her camera off.

All we can see is a black box with her

name on it being highlightedby a green line.

As she speaks, she takes a moment to think and then,

the pandemic brought out a lot of thingsto the surface that have been bubbling

along for a long time which everyone hasbeen too busy or not bothered about.

Lack of support and funding to the NHS

sustainability and environmental issues,the fact there are huge sections

of the society unfairly treated and people's outrage to that.

I think we've been through a long periodof time where it's been all me, me,

my little family unit, and notreally caring who lives next door.

And I think people have started to see

that it's more important to look outside of your own front door and interact.

Olly probes a little further,

asking about how these things have affected her personally,

the NHS, right at the beginning,there was the whole Rainbow Walks thing.

I don't know if you remember?

My kids drew their own to show theirsupport and they noticed there weren't as

many windows as they expected,filled with rainbows.

We talked about it as we were walking

around, trying to come up with reasons as to why that might be.

For them, it was the first time they'd been a part of something that goes

beyond their little school life, home life and it was a disappointment

for them to see that not as manypeople cared as much as they did.

Because, you know, kids have a reallygood sense of right and wrong.

And then the Black Lives Matter things.

For me, it was this sense of horrorthat we were in that situation.

You have to be careful what you put

on children's shoulders, but it did come up in conversation.

They definitely recognise that things

aren't working, but it's how you fixthose things, is where they felt stumped.

The final woman seems excited to speak.

She's got this little bob of grey hair

and she offers affirmations while otherpeople are speaking in the form of oombs.

She's got this big smile across her face

and it's been therethe whole conversation.

Her camera sits below her chin and it's

aimed up at her face,which makes her smile seem even bigger.

On breaking the rules, she says,and immediately giggles.

One of the times we were allowed to meet,we had a picnic in my garden.

My daughter came with my grandchildren

and I got chairs and we tookfood downstairs and everything.

And my grandson said he needed to go

to the toilet and I came up with himand we had a cuddle.

I said to him, you don't mind, do you?

Let's have a cuddle, darling.

I haven't seen you for monthsand we just had a little cuddle.

He jumped on my bed and wegrabbed each other and ugh...

for goodness' sake.

She appears to well up a littleand then regains her composure.

And it was the only timewe'd broken a rule.

That was it.

But that was nice, you know,being a, a, a rebel.

Okay, so this is our last story

from part one and we've calledthis story 'I think that will do'.

We are in a community centre on the borderof Islington and the City of London.

We are with a group of women who meetregularly to talk to one another,

listen to one another and have lunch with one another.

The room sits in a low, cool light.

On one side, large sliding doors reveal

a vegetable garden outside,abundant well maintained.

The woman who runs the group, who works at the community centre,

speaks with a soft Scottish Accent I rana food bank from day one of the pandemic

and we watched peoplequeue and we had no food.

Seeing people financially struggle,I've seen people that were so embarrassed

that they were in a situation wherethey had to come to get food.

I know of people where,

people who are working, who are watchingwhat they buy to eat, who are struggling.

For example, my daughter,she's the breadwinner.

She's on a good wage, but with childcare,

they got a mortgage justbefore the pandemic.

I'm helping her out with food,so that has an impact on my finances.

And she's proud,but they haven't got it nearly as bad as

the people I work with on a daily basis,people I'm in awe of.

I saw this bizarre thing this morningwhere they were teaching how to cook

a cheap meal quickly so you don't haveto use as much electricity or gas.

And I thought, My God,is this what it's going to be like?

Dealing with people who were frightened

and scared because they were angry,they were in a situation.

I found that dealing with them

with kindness, kind kind kindness, just wins over everything.

I think I'm a nicer person now.

I get less stressed about thingsI don't want to see.

I've changed the way I look at people.

I've seen people that I thought were not

very nice and realised that for every person's behaviour, there's a reason.

And that's changed me.

When we were first doing the food bank,

we'd have someone that would comein who'd be really degrading.

I want that, that that, theywould not say please or thankyou.

But we kept going and within about six

months, she was cracking jokes with us,cuddling us, bringing us gifts.

We just kept being kind.

And she, pauses for a moment,

goes to start speaking again,then says, and I think that'll do.

It feels like the whole room takes anintake of breath, holds it for a moment.

There was an emptiness.

All the buildings were empty.

Another woman says, speaking softly,and people go into themselves.

As soon as you talk about it,you can sort it out and be happy,

says a woman whose voice is soft,but whose accents makes it zing into

the air, and help each other, everybody needs help, you know.

There's my friend,

I recently phoned her and she couldn'trecognise my voice, you know.

I was worried, I said, what's going on?

We used to go to the same schooltogether, so I went to see her.

When I saw her, I was so shocked.

She can't remember things.

They often get a carer to look after her.

All her children have grown up.

The husband left her.

So I said, what's going on?

What can I do for you?

And when I came back home,she rang me to say thankyou for coming.

I said, don't worry, I'm therefor you if you need any help.

Don't worry.

You do what you can for people,because then when you look back...

It's been such a profound thing.

Another woman energeticallyannounces, it has altered me.

It has made me it sounds cliched,

really, but it sort of makes yourealise, you know, what really matters.

And actually, what matters when it comesdown to it, is your family, your friends,

your community, and caring for eachother and being there for each other.

And actually, that's quite simple.

It's quite hard to put into words a lotof this, and I feel like we need time.

There are great lessons to learn from what

has happened, says another womanspeaking clearly and slowly.

I feel that if we learn,the future will be good.

Thanks for that, everybody.

So that's the end of part one.

We've heard three stories.

What we'd like to do now,before we move on to the next section,

is to hear about what peoplehave been talking about.

When we do this work,

when we do these stories, we run these workshops, we do something like this.

We're trying to build a conversation

and build people's awareness of the conversation.

So we'd love to hear people justto report back on any

of the conversations that theyhad about any of the three.

All of the stories contained almost word

for word conversations that me and my friends have had.

And it brought home those connections

to me that everybody was in the same boat,everybody had the same experience,

everybody was lonely,everybody couldn't hug somebody.

And we were talking about the

disconnect between howcareful people were and how importantly

they took their role and whatthe government were doing.

And that anger that is still very,

very present for a lot of people,because the story,

like the grandmother who couldn't hugher child or did do it, in the end.

Everyone was terrified trying to do the

right thing, and the people who madethe rules weren't doing that.

Thank you.And I think tying into that,

I don't know if other people did,but it actually made me feel very

emotional because there's so muchthat we haven't worked through.

And I know throughout history,

after the war, we just sort of carried on and that keep coming, carry on.

But there's so much I could feel it

in other people when they were talking in the group.

There's so much emotionally that we're

holding on to that we're just not having the opportunity to work through.

It's almost like,

it's the draw a line under itand just go on to the next thing.

And it made me remember things that I'd

actually forgotten how I felt two years ago, that I'd actually kind of pushed

to the back of my mind and made me feel very emotional as well.

We spoke about the one rule for us

and one rule for themand the whole party gate thing.

We shared some experience with someof the things that we went through.

And even though that sort of bothered us,

that they're not obeying the rules,I think we were far, far angrier at things

they've done since and things notrelated to that, to be honest with you.

We're talking about in the middle

of the pandemic it felt like we were goingto come at the end

of it we were going to be,we'd have a kind of better world but it

feels like we've sort of moved awayfrom that again, if anything it feels...

We had an opportunityand we've missed it and we've moved away

from that and we seem to have revertedback to almost a type, really.

And to a certain extent it's the

way we've been led as a country orwhatever, there was an opportunity

for us, for the world to change,but I think we've missed it.

I think what it is,it's until you get to something like this

and you hear other people sayingwhat it is, but slightly different.

And when everyone thinks,

you're giving me thinking, oh, yeah, that affected me in this way,

or it affected my friend in that way,that's where you get something like this,

you suddenly realise howmuch it has affected people.

And I think it's just the way out to me,

the way that people have been brought upand all, it's like what you say, it's like

the way I would put my parents with my dadis men are not supposed to cry,

they can't show this,but it's not until you get shown it like

this and you suddenlyrealise, why can't I?

And why can't I do this?

To me, that's what it seems to me.

Kind of building on both those things.

It's such a beautiful space you've created

to reflect on this time that we've all been through.

I've also felt quite emotional actually thinking about it again.

But as a house, I live communally and wespoke about it a lot at the time.

But then when things started opening up.

I also was part of

the same thoughts of wanting to change and we got this opportunity and then

pubs and whatever opened up and I justwent back like the rest of the country

and forgot about all thoseconversations we were having before.

So it's been really nice to think aboutthose things and we had been talking

a little bit aboutthe things that you were saying.

About the things that you feel likehave stayed with us a little bit.

Fragment of the things

that we felt way more during the pandemicwith not being able to interact

with people and taking thingsfor granted as well

we've kind of gone back to where we werebefore but little parts of it have stuck

with usand that's some sort of constellation

in that, that we have takensomething away from it.

We appreciate hanging out with peoplemore than we have before the pandemic.

We appreciate even being able to visit

restaurant for a mealand we didn't necessarily appreciate

that kind of stuff before becauseit was never taken away from us.

So it's not like all is lost we,

have taken some of it, we should have taken way more.

But, it hasn't all been in vain.

It strikes me now that we've almost been

invited to return to the groups that we were in before

I mean you've got strikes now which leadsto a division, we have the war in Ukraine

so we have our enemies againand in every kind of situation we're

reverting to type and like our friend hereI only hope that we remember that we do

have the capacity to be like that,to be community minded, to be aware

of other people's feelings and situationsI feel that society has pushing us back

into our little groups so we can carry on as before despising

the people we despised and fightingthe people we fought then.

Following up on that and following up onthe name of one of your stories,

is that in that environment where we areall going back to the structural problems

we had before and even magnifying themthat this feels like an act of rebellion

actually that sharing these storieswith people you don't know from different

places feels like an importantact of rebellion.

And I think carrying on from what you said

I think that a lot of people are nowlooking outside of the given structures

for political or social rebellion and change and that they're actually

working like, they're looking outside the box basically

and then they're looking and finding waysof rebelling and building

alternatives that aren't within the given political structure or the power

structure and stuff like that and I think that's the way forward and that came

from COVID where we had like COVID organised support organisations and we

had like food banks organising voluntarilyto get people to bring food and stuff

like that so we've seen that there areother ways that we can organise that it

doesn't have to be in a party political or a power structure kind of way we

don't have to do it from within, we can do it from outside

that's something I think hascome through quite importantly.

Thank you Would anyoneelse like to say anything?

Before the pandemic even started I was

living aloneand I didn't have much social interaction

I've never needed that as a person but sowhen the pandemic kicked in and people

were talking about how they missed thingsand how it's affecting them,

I couldn't really relatebecause it wasn't affecting me.

I was still living the alone,

was having very little social interactionand it was just more of the same.

But hearing all these stories and speaking

to people how it affected them as it waseven happening, made me

realise to an extent how much wasmissing from my life as well.

So the whole pandemic,

as bad as it was on a personal level,kind of changed, it changed all of us,

but it changed a lot of meas well, for the better.

And I think on some level,

it's done that to many, many, many people who've again come

to appreciate and be more aliveand want to do more things, get out more,

see people more and kind of returnto instead of being in the box

and the status quo, daily life,kind of just be alive.

And that is a really good thing.Thank you.

I actually feel like we've covered a lotin that short period of time and a lot

of different territories,so I'm going to pause it there.

Thanks.

So we're going to move on to part two,which is our second set of stories.

Before we do, thank you all for your

generosity and clarity there in that conversation.

So we're going to move on tothe second set of stories now.

We've called this first one 'I miss 2019,when everyone was at the beach'.

I have a whole lot of complaining about it.

Young girl with blonde hair tiedin a ponytail, wearing a school uniform,

which gives the impression of once beingneat says, she speaks very quickly.

We are with three children at a community

centre cafe in the City of Londonat an after school club.

One year six, two year sevens.

We sit by big windows that lookout onto a busy road.

As the children sit with us,

they fidget trying secretly to eatKitKats and other snacks as well.

We explain.

We really don't mind if you eatin front of us, it's okay, guys.

The girl goes on with her complaints.

Everything was rubbish.

They made us work from homeand my sister kept pulling my hair.

A small boy with long hair interjects.

It's not her fault, senda letter to Boris Johnson.

I will, I will.

She says we only had one deviceto share and she wanted to watch TV.

A lot of shops were closed, it was veryannoying having everyone back at home.

I like, my dad going to the officebecause he brings back snacks.

It was horrible.

The boy shares his experience.

I had to go to school and do a fullday because my parents were working.

There were only ten of us.

We had to do an extra 3 hours of school.

There is another girl who speaks slower

than the first,but still at quite a speed.

And her uniform is a little neater.She says.

Before COVID, I was 2020 vision,now minus two because of computer.

We asked, do you thinkthe world has changed forever?

She says, I'm not sure, I'm not sure.

If things go back to normal, I thinkwe'll all be dead before that happens.

Climate change is going to change at all.

And how does that make you feel?

Sad and scared, because I missed2019 when everyone was at the beach.

I remember watching a documentary Iwatched about how wildlife

and the environment got better duringCOVID, the fast talking girl announces,

and in India you could seemountains you couldn't see before.

Things went really well for the animals

in COVID, but it's going to go back to normal.

But COVID has slowed it down.

She stuffs some food in her mouth,chews and goes on speaking.

It's kind of nice,

but annoying, some things change forthe better, some things for the worst.

The boy says, I remembered I never got

to see my friends and I usedto feel lonely at home.

Now I have loads of friends, but inthe pandemic I only had one or two.

I changed my accent, I used to be the type of girl who would

wear pink and skirts,now I don't, now I wear trousers.

I used to be someone who playedlots of sports, and now I don't.

With sports, I couldn't do any,

costumes I decided to stop dressing upand wear clothes that were comfortable.

And I couldn't get to talk to people,so I wasn't bothered to talk.

Agree or disagree?

The future will bebetter than the present.

You never know what the future holds.

Says the fast talking girl.

It will be better, says the boy.

Boris will get fired.

It's not going to get better,

says the girl, who's a little moreneatly dressed because of climate change.

Oh, she adds, I think it might get betterbecause I'm going to go to Southend.

This next story is called'The knock-on effect'.

Agree or disagree?

I am happy to talk about the pandemic.

A young woman half smiles,

doesn't say anything,but holds up her hand and does this.

Well, says a young man wearing a black

T-shirt artwork of a heavy metal band splashed across it, long hair.

There are things I want to talk about.

There are certain things I don't want to talk about.

We're at a youth centre somewherein a rural part of Redbridge.

It's evening, but the late springsky outside is still light, soft.

Inside, everything is really bright.

There's a TV on mute,two pool tables, colour pencils.

Every inch of wall is filled with colour.

We're at an evening club for childrenwith special educational needs.

There are about 15 of us sat round

the tables that have been pushed together,people from many generations.

There are almost as many support workers

sitting around the tablepas there are teenagers.

Agree or disagree?

The Pandemic has changed the worldand it will never be the same again.

If Boris just woke up and feltthe damn coffee, he'd know what to.

Do, says one young man in a very animated

fashion, as he does so, beaming at everyone else.

We've got our first mention of Boris,

says Olly, always delighted when his namecomes up, the animated young man replies,

but this time speaks with alittle less umph in his voice.

I just wish it was like before, whenwe would go and see who we wanted to.

It's not been all bad, says the woman who coordinates the group.

Everyone else around the tableintently listening to her.

There have been some good things about it.

People are more aware of hygiene now.

People wash their hands more now,

although the queue for the men'stoilet seems to have disappeared again.

Do you remember earlier on in the pandemic,

the cues for the men's toilets got long,but now they've disappeared again,

which I take to mean that menare not washing their hands again.

People laugh, a couple of the malessat around the table protest.

The women were probably stealingthe toilet roll, says one.

There's a sort of poll conducted directingat the men and young men around the table

asking whether they wash their handsafter they've used the toilet.

Yes, I do, says the animated young man,

sounding like he's readinga prepared answer from a script.

I even had a shower before Icame here, shout someone else.

I think the world has changed and I think

that every day, says one of the supportworkers, slouched shoulders, she sits

further back from the tablesthan everyone else.

I work in social care.

I look after people with mental health andlearning difficulties in their own home.

So even just going to work was scary.

All my staff were anxious,

I was really anxious and it affectedall of us in various different ways.

And up to today, it still does.

For my role as a manager, the pressurewas immense, I can't tell you.

You got the government,

you got the council, you got parents,friends, the residents themselves

and my team and the manager tellingyou what to do and what not to do.

And things are changing so rapidly,it takes a toll, a really big toll.

The room is very quiet.

She goes on.

So I lost quite a few people close to meand I've seen someone who lost their job,

who was also close to me,broken to pieces.

Money was really tight, it was really,

really difficult for them and that hadan impact on my life as well.

And I think for me, I just had to put this

facade on, pretend everything's okayand just continue on with everything.

Supporting people like I do in my jobs,

you need to make sure that theirmental wellbeing is okay.

If you show that you're breaking down,it might have an adverse effect on them,

so you have to makesure you're doing okay.

It's called the knock-on effect,

says the young man wearingthe heavy metal t-shirt.

That's right, she says,and then adds, it's tough.

How are you doing today?

I'm okay, she says.

I think so.

She leans towards the table, takesa chocolate and pops it into her mouth.

The conversation moves on.

The young man who mentioned the knock-oneffect says what's on his mind.

A lot of things, really.

I'm not saying that if anyone lost anyonebig whoop or whatever,

because I lost someone during it too, soI know how that feels and it isn't nice.

But within human history we've defeated

these things and we've bounced back from them and everything went back to normal.

He punches his hand as he says this.

So who's to say we can't do the same now?

It might not happen in our lifetime, itmight not be in our kids lifetime,

but it will happen eventually, in my opinion at least.

Thank you, Anna.

Okay, this is our last story.

It's called 'Stronger, but I'm getting old'.

We stand outside a community centre

in the heart of a housing estate in the City of London.

As we press the buzzer to go in, we realise this is the first in person

workshop Olly and I have run together in two years.

We look at each other,breathe and walk into the building.

This is a weekly socialgroup for older people.

We're greeted by the group's organiser,a woman we've met before.

She has a big smile on her face,

streaks of blue dye in her hairthat were red the last time we saw her.

She hugs us.

She tells us this is the first timethe group are meeting together in person,

in real life,since the beginning of the pandemic

and says that we must stayfor fish and chips afterwards.

We walk into the room wherethe workshop is going to take place.

Tables are moved to create a bighorseshoe and name tags are given out.

The older people arrive,

some moving slower than others,some being helped by volunteers.

People chat to one another,

find a spot to sit, some balancecanes on the wall behind them.

Cups of tea are offered and brought

to anyone who wants oneby an efficient bundle of volunteers.

Olly stands in the middle of the horseshoe

of tables and asks: Can people tell me ifthey agree or disagree with the following

statement I am excitedto talk about the pandemic.

People grown put their thumbs down,

there's, even some booing,Olly remarks, this is the first workshop

we've done in real life for two yearsand 2 minutes in, I'm being booed.

And so, for the first time in two years,we deliver a workshop in real life.

A workshop we've carefully designedto get people talking about the pandemic.

And everyone steadfastly refusesto say anything about the pandemic.

But everyone, it appears, is veryhappy to talk about everything else.

And they do.

Over the course of answeringthe first question.

Agree or disagree, the world has changedand it will never be the same again.

Almost every topic under the sun is

mentioned the climate emergency, issueswith neighbours, books, which books?

All the books.

The internet,

previous and future generations,the social order, but not the pandemic.

In fact, people talk at such length

that by the time we get round to asking the second question, agree or disagree,

I have changed and I willnever be the same again.

There's very little time for people

to answer in full, so instead I ask everyone to say one short sentence.

I'm changing, I'm beginningto look like my old man.

I think I've changed for the better.

I think I've learned a lotmore as I've got older, yeah.

Stronger, but I'm getting old.

I have changed because when I was younger,I was the mouse behind the door.

Now I say what I think and I don't care.

I've changed and I considerthat I've changed for the better.

I've changed, but I don't know into what.

Changed is a great deal.

I used to go out and do everything,

but now I just stay at home and goto the park across the road, ugh.

I've changed, we used to be peoplewho went to the theatre,

we used to see Shakespeare most of all,and now it's been two years at least more

than that, since we've seen anythingand I think that's a great shame.

I've proven myself.

That's an important statement.

Someone else says I haven'tproven myself at all.

I feel very content.

That's what I was going to say, we've done

so much with our lives that we could go tomorrow and we'd be happy.

That could be arranged.

I feel a bit calmer these days.

As a youngster,I was in the military for nine years.

Then I went to the NHS and I saw a lot

of death on either side and it used to worry me.

Then eventually I went to India

with the Dalai Lama's office and studied meditation.

And now I try to live in the now and I don't worry about the future or the past.

Now I said I didn't think I had changedand the reason for that is I'm still kind

of raging, trying to stay the young personI used to be in charge of everything

and in control of everything,and I suspect age is going to take

that away from me before too long,but I am still raging at the moment.

Well, I just take life as it is and it'sfloating along and as it keeps changing,

I adapt my condition to the change, takinginto consideration what is best for me.

Yes, of course,we've all got older and it's sad that we

can't do the things now that wewant to, but reality kicks in.

Have I changed?

I would say a bit late in life, but I'mgoing through that phase now of change.

What is possible.

What do I want?

Can I do that?

Check in with me next yearand I'll let you know.

Okay, someone shouts,time for fish and chips.

And fish and chips are served.

And we and everyone else sit togethereating fish and chips and talking.

Just like we used to.

Thank you, Anna.

Okay, thank you for listening, everyone.

So, as we did before.

We'd just love to hear some of whatpeople have been talking about.

Would anyone like to share?

All is not lost, thank goodness.

The stories you just told was quite

different from what I was expectingbecause you know the bit,

the one about the teenagerwho wants to go back to the beach.

I'm sorry, but it justmade me so much laughter.

And I think when you guys tell a story

but it really does get to me because I'm

thinking you're making us taking it all insometimes really does get to you.

You think,

wow, I wonder what it's like to be that person, like

the school child or theperson who was doing the thing with her

daughter about the money situation,things like that.

And I've really come to terms that Ithink this has been absolutely fantastic.

A question of everybody here and ask,do we feel like survivors?

Is there a sense of havingbeen through something?

Do we feel like we've dodged a bullet?

I think older people aresurvivors every day.

It's not a new thing for them.

But then again, we've all got throughit and this is how we are now.

Have we?

The fourth and fifthstrain are on their way.

Germany are discussing mandatingmasks from October to April.

So I'm not so sure that it's over, folks.

The fat lady has not yet sung.

So I hate to be the doom,but there is a question mark about how far

we are through it or ifwe're through it at all.

So, I've got my mask in my pocket.

I'm gona keep having a mask in my pocket.

I'm still going to wear iton the trains and theon buses because I've

not got it, she's not gotit and we don't want it.

Thanks very much.

I don't care what people think about mewearing a mask, I'm going to wear a mask.

It's my act of rebellion.

That's just it though, init, nobody knows if it is over or not over.

Something that really resonated with me,which is that ties in are we survivors?

Which is that really we've all beenthrough a collective trauma

and it was a trauma, but I don't knowthat we're now treating it that way.

Trauma takes some getting through and

societally we haven't put the steps inplace to help everybody get through that.

People might have done their own

individual work or got some supportfrom their family or friends or done

whatever they needed to do,but on a structural level,

we've not been given the tools or the helpor the space all the time to process what

we've all been through, becauseit's not productive to do that.

And everybody in charge has wanted us tobe productive again as soon as possible.

But I think there's a lotof unresolved stuff going on.

I think you're right about productivityand I think productivity and profits

in greed are at the basis of what you weretalking about, people not wearing masks

and masks now being almostlike a symbol of rebellion.

And the gentleman in front was saying

about how no one knowswhether it's over or not.

I think these are conscious messagesthat are being put forward into society.

Sorry, I'm just still getting overCovid and I get a bit breathless.

They're being put out into society

in order for us to thinkit's over and go to work.

I don't think we are going back.

I don't think you can go back.

I think we are going forward.

And I think, we were talking on the table

earlier, a few of us, and I think that we're actually

the vice is being tightened and I think a lot of people's experience of life now

is getting harder and tougher and more brutal.

But I think that this is a consciousdecision in terms of they want us to go

to work, they want us to use some public transport, they want us to do things

without thinking that there'sgoing to be any risk to us at all.

So we can't look at the trauma,because if we look at the trauma,

then we will take lessons from it,we will learn things from it.

And that's not, I think,

sorry I sound like some conspiracytheorist, but I think that it's not being

done, no-one's sitting down and thinking, oh, yes, let's do this.

But I think that'sthe way it's panning out.

We can't afford to,

we have to kind of even pretend that it'sgone or nearly gone,

because otherwise we'll never,as a society,

move out of the hold it's had on us,because everything kind

of ground to a halt and we have to start moving again,

even though it might notbe completely gone yet.

But everything didn't grind to a halt.

There was an alternative, wasn't there?

When someone was talking earlier,

I had in my head the vision of,like, William Blake, like heaven.

And to me, that's what itwas like in the lockdown.

It was like we were talking about earlier.

The skies were still, the people couldhear the vibration of the earth.

People generally were being very nice toeach other and very kind to each other.

So things didn't grind to a halt.

An alternative was glimpsed and it's almost like we've got to take that away

from people, because otherwise,why are you going to be a wage slave?

Why are you going to put up with all our

rubbish if you know that you don't have to?

There has to be some mechanisms

that enable it to, that let us affordto sit down and take a step back.

Only if you livein the capitalist society.

Which we do.Yes, we do.

And I'm the facilitatorof this conversation.

I go here and then we'll go here.

The second batch of stories was very muchlike I thought, yeah,

we could kind of put yourselfin the shoes of the people speaking.

You might be different age bracket

and the feeling of the young kids talkingabout climate emergency,

but also making connections between someof the answers, how you might solve that.

Maybe we're in COVID because they were

talking about how it's actually good for the animals.

That was a very sweet way of putting it.

But the notion that that is very consciousin the minds of people of that age

and it links back to what some people havebeen saying about things aren't over

in the sense there's another challenge that's ahead of us.

I was reflecting on that and howthey might manifest in similar ways.

And in France last week,

when it was so hot on Friday,it was like 41 degrees in the city.

They had to cancel events because you

couldn't be indoors in non air conditioned venues and stuff.

So events over a certain numberof people had to be stopped.

And I hadn't ever thought that that mighthappen for things to do with temperature.

Sort of like a little lockdown,

a mini lockdown, for temperaturereasons, not for COVID reasons.

Yeah, part of my job is working

with residents on estates,which meant I knock some people doors

to regard their building work that was going on.

And I found that the estate I was workingon then,

talk about how things came to a halt, Iwas working through a lot of it.

And when you knock on someone's door at

09:00 in the morning and when you asked the question - how are you?

And I was very disturbed because

that was a simple question, and the amount of people who would

actually burst into tears by the thought of saying, how are they?

It wasn't just fine, it was like, oh,

I've got this to do and that, and thenit's Covid and so many people cried.

I felt like I was asking like a deep personal question.

I have to say that I have my own copingmechanism there that I gained from this.

I go into cinemas and shout fire a lot.

Okay, so we're coming to the endof our allotted time.

Should we give ourselves a clap?

Thank you all so much for coming and beingso generous with your listening and your

talking and the conversations we've been having.

We will be launching a podcastof which you'll hear these stories and you

may hear snippets of the conversationsthat you've had today.

And we will be doinganother show in Redbridge.

You, Me, the World & This Moment wasconceived and delivered by take stock

exchange and was funded by Arts Council England, Poplar Union and Vision Redbridge.

The project happened with the supportof nine different community organisations

and their participants from acrossEast London, \the names of which we wont

reveal to ensure people'sidentities are protected.

But guys, you know who you are and we

thank you so, so much for being a part of this.

This podcast is edited and produced

by Penny Bell with music at the live events by Anna Lowenstein.

The project was created by take stock exchange.

That's Nick Cassenbaum,Olly Hawes and Anna Smith.

We'd also like to thank Isabelle and Ira, Morwenna, Sonny and Joss, Jessie,

JHohn Geisen, John Sheedy, Ben Abramovich,Ted Maxwell and Mary Osborne.

And again, to all the people wespoke to and you for listening.

We are living in challenging times and we

hope against hope, you are able to lookafter yourself and others around you.

You can find out more about take stock

exchange and our work by going to ourwebsite, takestockexchange.co.uk.

Episode 2 - You, Me, the World & This Moment - powered by Happy Scribe

We are recording!

People are moving

up, and even though it happened about twoyears ago, and people are going back

to their previous behaviour,like the men not washing their hands.

And also a lot of lives have been lostand um, people are still grieving.

I sort of felt that

when the pandemic things and law,rules affected me dreadfully.

I was used to going to a training

collegetoparticipate in classes and be with people

and have some mental stimulation,and we could go to art galleries

and museums and all thosesort of cultural things.

And then the pandemic closed it all down

and suddenly everything was sort ofmade so much smaller.

Hi there.

This is Nick from take stock exchange.

Welcome to podcast two of 'You,Me, the World & This Moment'.

This podcast is kindof like a bonus episode.

It's very much a follow up to podcast one.

So if you haven't listened to the first

podcast, please do so beforelistening to this one.

In a moment,

you're going to hear the voices of a fewdifferent people from me, Anna and Olly,

and also from different people who weworked with as part of the project.

And we all talk about the storiesyou heard in podcast one.

We discuss what each of the stories made

us think about in terms of the pandemic,where we are now and where we're heading,

and hopefully it will giveyou a chance to do the same.

Enjoy.

Okay, let's startdiscussing these stories.

So we're going to discuss them

in the order in which we told themat Poplar, which is the order

in which people at Poplartalked about them in response.

The first story was called 'One rulefor one, another rule for another'.

And it was aboutthe time we visited a men's social club.

A social club that happens

in a community room somewherein a housing estate in Poplar.

Do you remember when COVID started and it

was mandatory to wearmasks wherever you went?

Right.And at the time, some of us were standing

on the doors to make sure people comein and had their masks on and that.

Where my store is, we're right acrossthe way from the Walkie Talkie building.

Right in the centre of the office people.

You'd be surprised howmany rude people there is.

One of them even told my colleague to Foff just for asking him to wear a mask.

I think this story really captured a

sense of confusionthat we've been living with since

the beginning of the pandemic,and the sort of fluctuating...

the way in which we've been encouraged,ordered to behave and react to it,

and the constant changesin those messages.

And how sort of difficult those changing

messages have made socialinteraction with others.

I guess like,something happened to me the other day

on the train, which sort of made mereflect on this story a little bit more.

I was sitting on the train wearing a maskand a man got on the train and he wasn't

wearing a T-shirt and he'd obviouslybeen drinking quite a bit.

And he sort of started shouting at me,asking me why I was wearing this mask.

And I needed to stop wearing it because it

was making him insecure and itwas making everyone insecure.

And COVID was over.

And he got off at the next stop and as he

got off, he turned around to me and hesaid,

"The government's collapsedand you're there wearing that mask."

It was a couple of days maybe afterBoris Johnson had finally left office

or been told that he wasgoing to leave office.

And there was a sense of chaos in the air.

And this sort of interaction with this man

really encapsulated that sense of chaosand the changing parameters of what's

right and wrong and the strugglethat instability puts on individuals

and the way they interact with one anotherand the kind of tensions that that

sparks on the street when we'reinteracting with our fellow citizens.

Let's hear from you.

I want to focus on onespecific aspect of the story.

So sometimes people have reasons as to whythey don't wear a mask, but, for example,

medical reasons,like asthma might be a reason to break

that rule,but however, some people might take

advantage of this to not wear masks,which could be considered like immoral.

So I think people should be moreaffectionate and sympathetic towards

each other insteadof judging them immediately.

I think here it comes, like reputation,how you put yourself in a status.

I think this law, like all the laws,

according to your status, where would youput yourself and how confident you are.

So like,if I thought that my status is very high,

I've got high reputation in my family,in my community, then I might not do

some of the rules because I would thinkthat they're not acceptable for me.

As kind of the governmentor the Parliament did.

They thought that we made the rules,

we are in a high status,we have a high reputation,

so I think if we do anything, thenno-one would say anything to us.

Whereas people like us, even in ourself,we have a status in our family,

in our community or organisation,and mostly, if we're in a very high status

in our community, then we might thinkthat, oh, why am I scared of this?

If I stop following this rule,then I'll be counted as coward or

maybe like masculinity or my genderrules will not apply to me.

Because Masculinity is like about strong

and I'm a strong man, then whydo I need to follow these rules?

But it was not like that.

You had to follow the rules throughout.

I guess what kind of highlighted to memost in this story was the real sense

of injustice that the participants feltabout the fact that it's one rule for them

and one rule for another, one rulefor us and one rule for the politicians.

And I think as I was listening to Anna's,reflection, to me this kind of became

clear in terms of that,that the politic of the people in charge

exists to give us the impression that wecan do what we want whenever we want.

People say it's my life, I'll do what Iplease, It's like the politicians,

they can't say, you must do this, butactually I'm going to do something else.

People say it's my life.

I'll do what I please.

But it doesn't work like that.

But actually, what ends up happening is weend up policing each other because

there is so much chaoswith the rules and the law.

And what that ends up meaning is we don't

notice, really,when the politicians are having parties,

but also when they are buying upthe most of the UK and allowing their

property developer matesto get off the hook, etc, etc.

Then getting on a train becomes

a tense thing because we're all lookingsideways, but we're not looking up.

And that's very handy for the politicians.

Yeah, I just think it's quite interestinghow the people that made the rules are

the people breaking them with, I guess,how we were talking about less acceptable

reasons and more acceptablereasons to break rules.

Like it's not okay to, but there's moreacceptable, less acceptable reasons.

And the people that made the rules arethe people breaking them with the less

acceptable reasons,whereas the people following them,

even when they don't want to,and even when they're going through tough

times, are the peoplethat either wouldn't break them or would

break them for the moreacceptable reasons.

So I think it's fairly,

I guess you could say hypocriticalthat we were told to stay indoors and stay

safe, I guess, whenthe same people that told us that were

the same people going outand having parties quite often, so.

And I think this really struck mewith this group

and actually being in and amongst thisgroup really made me

reflect on my privilege of being,you know, a middle class, healthy man.

We've got a group of people who

are extremely vulnerable in lotsof different ways

and all of them were saying,we can't believe people don't wear masks.

And I was like, oh,

these are the people we need to belistening to in terms of making these

rules and making these laws, because theseare the people who are most at risk.

And I guess what was so remarkable about

them is that howmuch they wanted to have fun and enjoy

themselves,despite existing in a world where

they've got a palpable sense of no onereally caring about them,

apart from each other and their smallcommunity and being vulnerable.

I have a slightly different outlookon the story that we just heard.

So listening to this,I've realised that even though times were

difficult during the pandemic,we had a really strong community and like,

the world came togetherand understood each other.

And that really made me feel,

like, really nice to hear thatfrom a third person perspective.

And being in that situation, it was like,oh, wow, people understood each other

and came together and supportedone another during hard times.

The last line of this story is theman who runs the group

saying quite emphatically,people should look after one another.

And this was someone who had gone throughthe whole time that we'd spent together

being very mild manneredand softly spoken.

And then towards the end of our timetogether, sort of having heard the group

talk at length about stories abouttheir experiences of COVID and I suppose

experiences just outside of COVID,he became quite emphatic, he

became quite declarative and he made thisvery impassioned speech which culminated

with him sort of saying peopleshould look after one another.

When I was listening back to this story,

I was reminded of something that someonesaid at Poplar in the discussion part.

This person said,we're all in this together

and we're all in this together issomething that we heard a lot during

the Pandemic,particularly at the beginning

of the Pandemic when thingswere most extreme in 2020.

And I think my visit to this group

made kind of, in my mind,made a mockery of that statement.

I think it was so apparent, as you said,

Nick, the joy that existedin that room when we walked into it.

It's a pleasant room,it's got a little garden outside

in a courtyard, but it'snot the best maintained room at all.

And you go in and there are these peoplewho are laughing and singing and cackling

and shouting and bringingenergy and joy to one another.

And yet, both in the way these people sort

of appeared and in the way they talked,it's clear that they felt so vulnerable

and kind of felt betrayed yet againin the way that COVID had been dealt with,

in the way that it hadto become a class issue.

I've come to understand that social lifeor interaction, as we had in the story,

is about that you have to followcertain rules, otherwise it doesn't work.

In a sense thatif you don't want to follow the rules

with everyone,then go and live on a deserted island,

try and get yourself some food,some rainwater, some,

build your own house, start from scratchand then you can do whatever you want.

But we have the comfortable life here,

wherewe distribute chores and we will live,

in a way, harmonically together,where we all benefit from each other's

input and work,but it comes with a certain amount

of restrictions and social interaction andrules and conventions and laws, etc.

Which means you have to followto an extent, otherwise it doesn't work.

Okay, so let's go on to our next story.

Next story was titled: 'That felt good,being a rebel'.

It's the story of when we met agroup of writers on Zoom.

It's a group of writers we visitedon a number of occasions before.

We know the members well.

Essentially we are group animals.

We are not meant to live in isolationand zoom and meeting people

is not the same as actually giving someonea hug, unless you break the rules.

Did you ever break the rules?

Yes, she answers without leaving a beat.

Seeing my kids, my older daughterhad been living in America.

As soon as I saw her,of course I gave her a hug.

it's horrible otherwise.

I think that it deals with some

of the injustices that the first storydoes, but potentially in a different way,

especially with the first womanand the last woman in this story.

They both broke the rules,and they both were,

for most part of the pandemic,living alone.

And so I think that it's a kindof an important experience to reflect

of individuals whowere doing what the government said,

were trying their hardest to dowhat the government said.

But it gets to a point where you just go,I've just got to give my grandson a hug.

And I recall the first time we told thisstory to Anna and also Anna our musician,

and both of you had quitean emotional response to it.

That it was something that really.

I don't know, hit something,brought a feeling up.

Discuss about the hugging situation.

Colleague was saying that

we shouldn't break the rules, peopleshouldn't break the rules.

But I think, we're only human

and sometimes you dohave to break the rules.

And if you talk aboutfamilies, it's a bit difficult

for families like this child, nothusband, a lot more difficult.

Like if the food is therebut you're not allowed to eat it.

Because as human nature,we do have to eat food.

So it's human nature to huga child and the child would be

psychologically damaged, ifit doesn't get human touch.

So what is more important - the child'smental health or the rule?

Actually, for me, on breaking the rules,as she said actually,

it has a personal experience that hashappened for me actually,

because when I was here in London,like three years back,

it was more like the moment I stepped inthe next month it was lock down actually.

So I was away from my familyand it was like

close to two and a half years we were justonline, just a WhatsApp or something.

We just to see them and we used to talk

and with that being in place,I never thought I missed them.

But on the reality, when I went back and Igot a chance to go to my country

after two and a half years and when I sawthem, I couldn't control myself.

Like hugging them.I didn't do that, to be honest, because

it's what a human being we are at the end,and there are some times where

I think rules can be broken,are meant to be broken.

That's what my personal perspective is,on that.

Yeah, I'll jump in.

I mean, I think that this is a story

that involves threewomen talking about either explaining

the world or trying to explain and protecther children from the world or

hugging someone from theirfamily in a younger generation.

One of the times we were allowed to meet,we had a picnic in my garden.

My daughter came with my grandchildrenand I got chairs and we took food

downstairs and everything,and my grandson said he needed to go

to the toilet, and I came upwith him and we had a cuddle.

I said to him, you don't mind, do you?

Let's have a cuddle, darling.

I haven't seen you for months.

And we just had a little cuddle.

He jumped on my bed and we grabbed eachother and for goodness sake,

she appears to well up a littleand then regains her composure.

And it was the only timewe'd broken a rule.

That was it.

But but that was nice,you know, being a rebel.

And yeah, I thoughtit was a kind of almost quaint,

sort of emotional story that served asan example of how it can be right to break

the rules sometimes, how it ishuman to eat or to need a hug.

The first woman who spoke talked about

the importance of touch,of actual touch and contact.

And it sort of served as a counterpointto this kind of rampant rule breaking

and hypocrisy that was going on,not just in terms of parties,

but in terms of the way in whichthe pandemic was handled in a wider sense,

cronyism when it came to NHS contracts andall sorts of other things.

And yet the thing that first comes

to my mind when I think about this storyis the response of a group of teenagers

who we told it to,who are very, very clear -

they broke the rules,they shouldn't have broken the rules.

I really feel that it's very emotional.

But the thing is, you can't really breakthe rules unless it's life threatening.

Sothe thing is that they've broken the rules

and they can't be broken, I guess,unless it's life threatening.

Yeah, I guess obviously,

it's understandablethat you would want to see your family.

You would want to meet them and you wouldwant to sort of like get close to them.

But, like, I guess not really being

selfish, but you have to lookat the bigger picture.

Like say without knowing you hadCOVID and then you hugged your grandson.

And then your grandson passed on to peopleand people and the whole chain started and

someone could have passedaway or something.

I guess obviously, they

didn't really think of thatbecause it's, like, personal.

And they didn'twant to think anything like that could

happen by justmeeting with each other I guess.

It's only ok to break the rules if it'svery, very necessary.

Okay.For example, if someone is dying.

Yes, I was really emotionalwhen I first heard that story.

It really returned meto a kind of state of being that was so

prevalent throughout the first, perhapsthree or four months of the pandemic.

I remember the place that I lived

at the time, me and one of my housemates,we'd have this thing called 'Dilemmas

Club',where we'd like to have a cup of tea

together in the morning and discussCOVID related dilemmas.

And we had so many conversationswhich were about, like,

to what extent was it okay to kind ofpush the rules if actually what you were

doing was somethingthat had kind of another benefit.

And I just think we were kindof completely immersed

for a good few months in that kindof thinking,

which completely infiltrated our psycheand affected everything that we did.

Yeah, I'd kind of forgotten aboutthat way of being, to be honest.

Yeah, it's so touching,

it's all thoughts and then because thingshave been calmer,

that I know of recently, somehowtry and not remember what's going on.

But it's true, life will never bethe same, it's made such an impact.

And that doesn't mean to say wecan't laugh and live, this is the thing.

But it's just, it's just been really hard,

it's been very emotional,what you've been reading out.

The last time we told this story wasto a group of older people

at a sort of older people socialclub in the City of London.

And a woman just sort of pointed herfinger and said: "Granny wasn't a rebel,

she was a human being."She wasn't a rebel, she was a human.

And I think that's probably a pretty good

place to finish ourdiscussion of that story on.

So let's move on to the third one.

We called it 'I think that will do'.

It's the story of our visit to awomen's social club...

When we were first doing the food bank

we'd have someone that would comein who'd be really degrading.

I want that, that, that.

They would not say please or thankyou.

But we kept going,and within about six months,

she was cracking jokes with us,cuddling us, bringing us gifts.

We just kept being kind.

And, she pauses for a moment,

goes to start speaking again,then says, and I think that'll do.

I think I think about thisstory actually a lot.

Maybe two or three times a week,I have this woman's voice in my head,

where she talks about the power ofkindness, respect and dignity,

and the struggle to do thatunder difficult circumstances,

but actually, likehow the significant change that can occur

if you pursue that courseof action relentlessly.

So quite often when I feel challenged,

I do have her voice ringing in my head,of kind of like,

can you just bring yourselfto treat this person with kindness?

Yeah, I think two things.

The first was that prideor the word proud of pride.

These people don't want tohave to rely on food banks.

They work hard.

And I think how you treat them.

It's so important that they keep theirdignity and they don't want to feel

that they're taking withoutgiving something back.

And I think the other thing is not judging

people the way that she said about thiswoman who was kind of angry and taking.

And there is always a reasonthat people behave the way they do.

Unless you're in their shoes,

you can't know andall you can do is the kindness be kind

to them and then they'llbring their defences down.

Nick, what about you?

I guess what I'm having now is like

a reflection on the structures thatmean that this woman has to do this job.

And I'm thinking in particular aboutmy partner's job.

She was a social prescriberat the beginning of the pandemic.

This is a community centre.

This is a place where people should gotoplace snooker, pool, have a cup of tea,

meet some new friends,get involved in the community garden.

This is not a place that shouldbe the only way that people get to eat.

And it says a lot for thenature of this country.

Okay, let's move on.

So our fourth story is the story that hasthe favourite title for me,

which is: 'I miss 2019 when everyonewas at the beach'.

I have a whole lotof complaining about it.

Young girl with blonde hair tied

in a ponytail,wearing a school uniform,

which gives the impression of once beingneat says, she speaks very quickly.

We are with three children at a community

centre cafe in the city of Londonat an after school club.

One year six, two year sevens.

We sit by big windows that lookout onto a busy road.

As the children sit with us, they fidget

trying secretly to eat KitKatsand other snacks as well.

We explain.

We really don't mind if you eatin front of us, it's okay, guys.

I think that age, sort of 12, 13,11, 12, 13.

Actually really accurately reflected,and the kind of candidness in the way

that they spokeand the way that they sort of flippantly

talked about quite challenging experiencesof the pandemic

and quite flippantly talked aboutexistential crises

that globally were facingI do think kind of reflects much more

broadly society and the way that,the experience that, like,

en masse we are sort of goingthrough at the moment.

Which is - very fast pace

new information, like new circumstancesarising, like almost on a daily basis.

And our reactions to them having to kind

of come very quickly and having to kindof change,

like with every new headline and every newkind of more and more wild

situation that seems to emergein front of our eyes.

And I think I feel like those teenagers

at the moment, you know,constantly experiencing all this new

stuff, constantly challenged by kindof like terrifying information.

And,yeah, I kind of think they captured

something about what actuallywas going through more broadly.

Let's move on to the next story.

It's called 'The knock-on effect'.

The knock-on effect was about our visitto a social club again for young people.

So we started this second partwith two stories about young people.

These young people were older,

and it was an SEND social club,a special educational needs social club.

And this was a story where we talked a lot

about the kind of, again,the joy and the sadness

that existed within the room whenthe young people were talking about it,

and then the story pivotedto one of the support workers speaking

at length about theirexperience of the pandemic.

It takes a toll, a really big toll.

The room is very quiet.

She goes on,

So I lost quite a few people close to me,and I've seen someone who lost their job,

who was also close to me,broken to pieces.

Money was really tight.

It was really really difficult for themand that had an impact on my life as well.

And I think for me,I just had to put this facade on,

pretend everything's okay and justcontinue on with everything.

Supporting people like I do in my jobs,

you need to make sure that theirmental wellbeing is okay.

If you show that you're breaking down,it might have an adverse effect on them.

So you have to makesure you're doing okay.

It's called The knock-on effect,

says the young man wearingthe heavy metal t-shirt.

That's right, she says,and then adds, it's tough.

I'm kind of maddened that the systemis such that this person

has so much weight on their shoulders,both in terms of their professional life.

She talked so much about all the differentdirectives coming from management,

from parents, from council,from government, from other regulations,

and the challenges that she wasfacing as a result of that.

I mean, this is not call on my part

for any deregulationof the caring industry at all,

but clearly it seemedto me there was too much.

And in addition to that, she had

the challenges in her personal life orthe challenges of the other people in her

personal life financiallyand her taking on some of that.

Anna, what are your thoughtsand feelings about this story?

I think on listening to the story,

I really could relate to the supportworker and kind of the quite intense,

like, layers of struggle that wasgoing on for that person.

She and her story articulated thatexperience,

that need to keep it togetherfor the benefit of other people,

which so many people,whether that was in their job or whether

that was for their family or their friendsor just other people around them,

I think so many people were kind ofproviding that support for one another.

All the community around here rallied

round In COVID there wasa whole WhatsApp thing.

If you need any help, we'll get it to you.

Hundreds of people involvedin it, the tiny groups.

And you always felt, I always felt that ifI really needed something, I

just get on there and someonecould find solution for me.

So people do rally around,but it's very interesting.

The other thing that's coming to mind is

the vulnerabilityof the young people in this group and how

some of them knew exactly what was goingon and spoke very eloquently about it,

especially the voicethat we put into the story.

But a lot of them were just like,I just want to see my friends and not

really knowing exactly what was happening,not being able to go to hospital to visit

their friends, presumably becausethey also had vulnerable friends.

And the injustice of that, that they fell.

What I thought was sad

was the awareness at such a young age,awareness what was going on,

and the awareness of what the futurecould hold because of COVID.

So I thought that was really sad.

Kids are resilient at the same time,like my grandson.

I didn't see hardly for them in that time,but just a lot when I did see them,